Dedicated as Young Memorial Hall on Jan. 8, 1909, Centre’s first building devoted entirely to science was named for two Centre presidents — John C. Young (president 1830-57) and his son William C. Young (1888-96). The two presidents continued to be honored when an entirely new Young Hall, dedicated March 21, 1970, replaced the first. The current Young Hall includes a substantial addition dedicated Oct. 21, 2011.

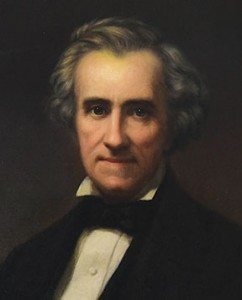

John Clarke Young, born in 1803, the youngest child of a Presbyterian pastor, grew up planning to follow his father into the ministry. He graduated from Dickinson College in Pennsylvania and from Princeton Theological Seminary in New Jersey, then headed west to lead a church in Lexington, Ky.

In 1830, at the age of 27, Young accepted the challenge of remaking a college in dire shape. Centre’s finances were precarious, and it had graduated just 24 students in its 11-year existence. Yet the new president had a clear and optimistic vision for the College’s role in the lives of its students.

“The proper object of a collegiate education is to increase the future happiness and usefulness of the pupils,” he proclaimed in his inaugural address.

Raising money, however, would be critical. According to a history in the 1857 catalog, Centre in 1830 “was wholly destitute of means.” Early on Young spent two months in New York City and Philadelphia prospecting for much-needed funds.

“The support of 2 additional Professors for the coming 5 years would be a great lift for us,” he reported to David Cowan, secretary of the Centre board, while in New York. “It would give character at once to the Institution as a place of large advantages, superior to any other in the West, and give us a few years to operate in collecting our debts and raising such additional funds as would make this enlarged Establishment permanent.”

Like all 19th-century Centre presidents, Young was also expected to teach, and he served the additional role of professor of moral and mental philosophy. He also taught belles lettres and political economy whenever the position was vacant.

A “small, spare man, his body . . . packed with energy,” as a later historian described him, Young added pastoral responsibilities when, in 1834, he agreed to lead the Danville Presbyterian Church and later the new Second Presbyterian Church. In 1853 he helped found Danville Theological Seminary, which maintained close ties to the College. That same year he was also moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church.

As president in the years leading up to the Civil War, he could not avoid the divisive anguish of slavery. Young and most of the faculty came from the North, while most Centre students were from the South. It took all his considerable skills as a peacemaker to keep the College moving forward during that tumultuous time. Young publicly argued in favor of the gradual emancipation of slaves and eventually freed those slaves who had come to him through his wives.

He was married first to Frances Breckinridge, with whom he had four daughters. After her death in 1837, he married Cornelia Crittenden, with whom he had six more children, including William, who would become Centre’s eighth president.

By 1857, when Young died in office, Centre was flourishing. Enrollment had grown to more than 225 students, including students in the grammar school. The year he died, the College graduated 47, its largest class to date. The endowment was more than $80,000. And the alumni roster included a sitting vice president of the United States.

“It was during the Young years that Centre developed a reputation as a producer of civic leaders,” wrote Centre sociologist Beau Weston in his 2010 book Centre College: Scholars, Gentlemen, and Christians.

During nearly 27 years as Centre’s fourth president, Young had worked a miracle.

“Dr. Young found Centre College prostrate and disorganized,” one of his contemporaries observed. “He infused life into it, organized it anew, secured for it an endowment, spread its fame over the whole country, filled every profession and calling with its alumni, and left it with its halls crowded with students drawn thither by the report of his wisdom and the fame of his learning.”

From his vantage point of more than 150 years later, current Centre President John A. Roush concurs.

“I am of the opinion that John C. Young saved Centre College,” says Roush, who has Young’s portrait in his office. “Centre, like a great many other smaller colleges and universities across the nation, was in a most fragile position during its first half century. In truth, there were dozens upon dozens of institutions like Centre that failed during the middle and end of the 19th century. But John C. Young stepped forward and would not allow that to occur on his watch. For his remarkable efforts we owe him a debt of considerable magnitude.”

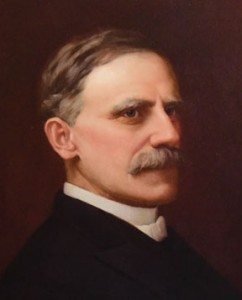

William Clarke Young was born in Danville in 1842, the son of John C. and Cornelia Crittenden Young. After graduating from Centre in 1859 and the Danville Theological Seminary in 1865, he enjoyed a successful 23-year career in Presbyterian ministry, serving churches in Covington, Ky., Indiana, Chicago, and Louisville. A “fiery orator” and yet “affable and approachable,” he was persuaded to accept the Centre presidency in 1888 when he was 46.

Under William Young’s eight-year tenure as president — and professor of moral philosophy and history — the College continued to prosper and expand. He added a law school backed by the prestige of the former Kentucky governor J. Proctor Knott as its head. The endowment reached $265,000. The College drew students from 15 states. According to the 1890 catalog, alumni to that point numbered nearly 1,000, including more than 300 lawyers, nearly 200 ministers, 80 physicians, 19 college presidents, 41 college professors, 14 representatives in Congress, 4 United States senators, 5 governors, 24 circuit judges (state and national), 37 editors, 1 U.S. vice president, and 1 U.S. Supreme Court justice.

Centre’s first gymnasium (Boyle-Humphrey Gymnasium) opened in 1891. Breckinridge Hall, though built by the Danville Theological Seminary, was completed on Centre’s campus in 1892.

And Young dreamed of yet another building. The trustee minutes of June 9, 1891, record his plea as chairman of the faculty: “An immediate and most urgent material need of the College is a new building to be used exclusively for scientific work, and an additional teacher to divide the instruction in this wide department with the one greatly overworked Professor who alone has charge of all these branches. The earnest consideration of the Board is asked with regard to this subject.”

It would take nearly two decades, but when the new science building at last was built, it would carry the Young name.

William Young also persuaded the board of trustees in 1891 to finally grant Centre degrees to the three of his half-sisters still living. As the daughters of the then-president, they had been allowed to complete the necessary requirements before the Civil War, but not to receive the official recognition they had earned.

In 1874 he married Lucy Waller. Sadly, her poor health kept them apart for much of the time until her death in 1896, just a few months before his own. Young died of a heart attack on Sept. 16, 1896, while preparing to hear student recitations.

He “could have commanded the most important pulpits of the land,” the trustee minutes noted after his death, “but his heart was in his work for Centre College to which his life was bound by so many & tender ties.”

He is buried in Danville’s Bellevue Cemetery along with his father.

by Diane Johnson

This article was originally published in the Spring 2015 Centrepiece magazine.