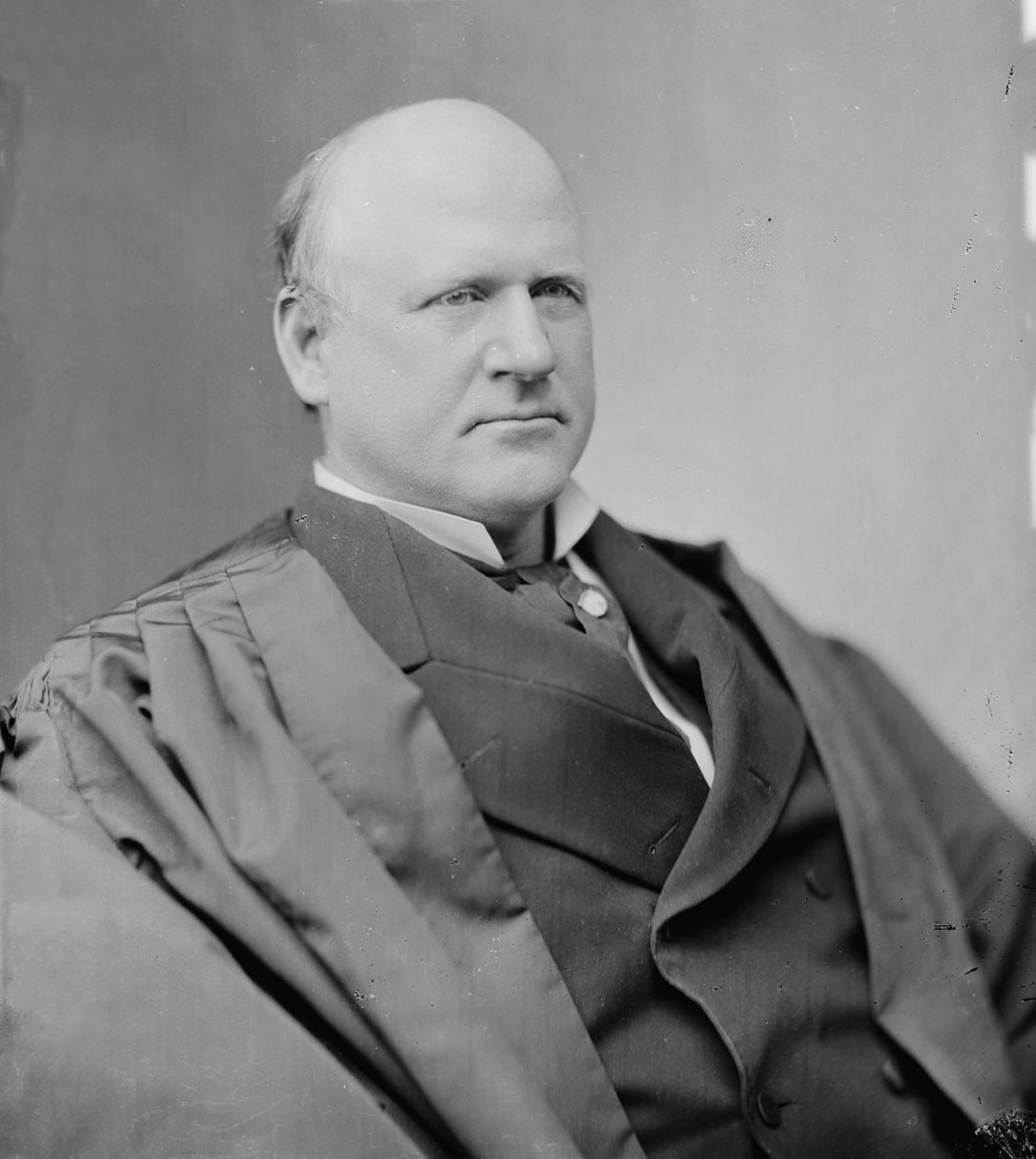

Centre’s Great Dissenter: The life and legacy of John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan was an unconventional figure for a U.S. Supreme Court Justice. He stood over 6 feet 2 inches tall and weighed 240 pounds. He wore brightly colored clothing, drank bourbon, chewed tobacco, and played baseball and golf in his free time.

He gained the attention of his colleagues and the media alike for his energetic and sometimes ferocious opposition to majority decisions with which he disagreed. The New York Sun reported on one such incident in 1895 during the Pollock v. Farmers' Loan and Trust Company when Harlan “pounded the desk, shook his finger under the noses of the Chief Justice and Mr. Justice Field, turned more than once almost angrily upon his colleagues of the majority, and expressed his dissent from their conclusions in a tone and language more appropriate to a stump speech at a populist barbecue.”

Like many men of his time, his legacy is a complex one. Raised in a slave-owning family and a vocal critic of abolition efforts in the lead-up to the Civil War, Harlan would go on to have a profound impact on the Supreme Court and the cause of civil rights in the United States.

Accused of flip-flopping on the issue, the future justice said during a 1871 Kentucky gubernatorial race, “I have lived long enough to feel and declare, as I do this night, that the most perfect despotism that ever existed on this earth was the institution of African slavery.

"Let it be said," he continued, "that I am right rather than consistent."

The lone Southerner on the bench during the Post-Reconstruction Era, he earned his reputation as “The Great Dissenter” for his spirited opposition to court decisions that threatened the newly won civil rights of African Americans. Harlan remains an enduring influence on the Supreme Court and a role model for scholars, jurists and activists.

The Great Dissenter

It was his robust opposition to a series of cases that infringed on the rights of Black Americans that cemented Harlan’s reputation as The Great Dissenter.

Anxious to avoid re-inflaming tensions with the South, the Supreme Court majority ruled in favor of efforts in Southern states to bring about legal segregation by circumventing the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments — adopted after the Civil War to abolish slavery, define citizenship and equal protection, and secure voting rights regardless of race.

Harlan forcefully opposed these decisions, declaring them to be unconstitutional and warning of their long-term consequences for the nation.

These decisions included the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, a series of cases filed by African Americans who had been denied access to public amenities and services. The court majority found that the Civil Rights Act exceeded the federal government’s authority. The lone dissenter, Harlan reminded his colleagues that the “supreme law of the land has decreed that no authority shall be exercised in this country upon the basis of discrimination.”

Another notorious Supreme Court decision was Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, in which Homer Plessy, a biracial man from New Orleans, was arrested for sitting in a whites-only rail car. The majority upheld Louisiana’s segregation law, approving the principle of separate but equal, which would be used to justify segregation and Jim Crow laws for decades to come. Harlan, the sole dissenter, rebuked his colleagues, writing: "In the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is colorblind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.”

In Berea College v. Kentucky in 1908, the court majority upheld the State of Kentucky’s efforts to enforce segregation at a small, historically integrated college. Harlan struck back, asserting that the case was not about changing a single institution’s charter, but the beginning of a statewide ban on interracial education. “It is absolutely certain that the legislature had in mind to prohibit the teaching of two races in the same private institution at the same time,” he wrote.

Unexpected for a white judge in the late 19th century, Harlan’s defense of African American rights offered Black Americans something they had not previously had — an ally on the Supreme Court.

“One of the most important lessons we can learn from Harlan is that you have to keep striving at it to get it right,” said Peter Canellos, author of “The Great Dissenter: The Story of John Marshall Harlan, America’s Judicial Hero” and managing editor for enterprise at POLITICO.

“As a politician, he took some positions that I think he later regretted, but he also learned from them. Harlan took his position on the Supreme Court very seriously, and he was willing to stand up for what he felt was right,” Canellos said. “In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, Harlan believed that the principles of fairness, equality and justice were equally applicable to Black Americans, even at a time when everybody else in positions of power disagreed with him. It was an extremely important assertion during one of the darkest, most troubling times in American legal history.”

His dissents earned praise from civil rights groups, including writer and activist Frederick Douglass, who wrote of Harlan’s Civil Rights Cases dissent: “I am glad sir, that in this day of compromise and concession… that you have been able to adhere to your convictions and thus save your soul.”

Politics and family

To understand the extent of Harlan’s transformation from an opponent of emancipation to a defender of civil rights, it is important to look at the influences and experiences that guided his personal and political journey. Born near Danville in 1833 to a prominent Kentucky family, Harlan was named for Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshall.

His father, James Harlan, was an attorney and politician who served in the United States Congress from 1835 to 1839, as well as Kentucky’s Secretary of State, Kentucky’s House of Representatives, and as Attorney General of Kentucky from 1850 until his death in 1863.

The Harlans were a slaveholding family, and James is believed to have fathered a son, Robert Harlan, with an enslaved Black woman named Mary. Raised with the Harlan family, Robert went on to become an accomplished business leader and civil rights activist who helped advance John Marshall Harlan’s political and judicial career.

In 1848, John and his brother James were admitted to Centre College, where their family had strong connections. John’s older brother, Clay, had graduated from Centre the year before, and its president, Reverend John C. Young, was the Harlan family’s minister.

Centre, with its emphasis on writing, public speaking, and the study of America’s history and institutions, was the perfect place for Harlan to hone his oratory skills. He later described Centre College’s influence, noting that Young had instilled a powerful sense of responsibility and conscience in his students. Harlan would later return to defend his alma mater from takeover by a Southern faction of the Kentucky Presbyterian Synod following its schism in 1861. He graduated with honors in 1850 and studied law at Transylvania University before joining his father’s law office in Frankfort.

In 1856, he married Malvina Shanklin, the daughter of an Indiana business leader, and they went on to have six children. Malvina’s unpublished memoir about her life with John, “Some Memories of a Long Life, 1854–1911,” was later discovered by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and published in 2001. In 1858, Harlan was elected Judge of the county court of Franklin County, Kentucky, which was his only judicial post before being appointed to the Supreme Court in 1877.

During the Civil War, Harlan fought for the Union, serving as a colonel in the 10th Kentucky Volunteer Regiment, but he believed the conflict was about preserving the United States rather than ending slavery. He opposed the Emancipation Proclamation and did not free the slaves he had inherited from his father until the 13th Amendment required him to do so.

In a dramatic turnaround, after supporting Democratic candidate George McLellan in 1864, Harlan joined the Republican Party in 1868 and became Attorney General of Kentucky.

Some believe Harlan’s change of heart was for political convenience. Others suggest his purported half-brother, Robert, and Malvina, who came from an abolitionist family, may have helped influence those views.

The Bench

In 1876, following two unsuccessful runs for governor, Harlan led the Kentucky delegation at the Republican National Convention in Cincinnati. It was here that Harlan’s future would be secured when he played a key role in landing the nomination for Rutherford B. Hayes. Hayes was elected president and appointed Harlan to the Supreme Court the following year.

During his 34 years on the Supreme Court, Harlan authored 745 majority opinions, 100 concurring opinions, and 316 dissents. He tackled issues that remain relevant to this day, including birthright citizenship, state-mandated vaccination and antitrust laws. He also taught evening classes at what would become the George Washington University School of Law, and a collection of his constitutional law lectures is now preserved in the Library of Congress.

Harlan was driven by his belief in the Constitution and the Supreme Court’s duty to protect the people from decisions that granted too much power to government institutions. He described this responsibility in 1902, saying: “The power of the Supreme Court for good, as well as for evil, can scarcely be exaggerated… It can by its judgments strengthen our institutions in the confidence and affections of the people, or, more easily than any other Department, it can undermine the foundations of our governmental system.”

In 1911, Harlan passed away after a short battle with pneumonia. The Washington Bee, an African American newspaper, wrote: “An entire race is bowed in grief because a friend has been taken from us. …Now that he is gone, we cannot help but tremble, and fear that no one after him may dissent against decisions against our race.”

For many years, Harlan was largely forgotten — an eccentric footnote in judicial history. But his dissents would provide a valuable framework for the arguments that saw the separate but equal doctrine unanimously struck down in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954.

For some, Harlan remains a complicated figure. Although he was a powerful early advocate for the rights of Black Americans and played a significant role in recognizing citizenship rights for Native Hawaiians, Puerto Ricans and people from the Philippines, he was not the ally to Chinese immigrants that he was to African Americans, leading to a questionable decision on birthright citizenship.

“I think Harlan’s skepticism about whether foreigners, accustomed to living under monarchies, could acclimate themselves to American self-government went too far,” Canellos told the SCOTUS Blog. “His views became much more moderate over time, and he took pains to repudiate his involvement in the anti-immigrant Know-Nothing party. But this vein of thinking never quite left him.”

What cannot be disputed, however, is that through his courage and convictions, Harlan had a lasting impact on the United States legal system and laid key foundations for the Civil Rights Movement in the twentieth century.

Harlan’s impact and his influence on the Supreme Court endures to this day. Chief Justice John Roberts keeps a portrait of Harlan in his conference room. The “Harlan Bible” — donated by Harlan in 1906 — has been signed by every Supreme Court Justice in the last 120 years. Justice Neil Gorsuch cited Harlan as his role model during his confirmation hearing in 2017. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson has spoken about her sense of awe when she took her oath holding the Harlan Bible, and Justice Sonia Sotomayor described taking her oath on the Harlan Bible as “one of the most symbolically meaningful” activities of her investiture.

“Harlan is a rare figure who is admired by people at both ends of the political spectrum,” said Canellos. “To conservatives, he is an originalist who had a deep understanding of the intent behind the Constitution, while liberals admire his commitment to providing a fair and just outcome for the people involved. He was able to balance these competing ideologies, while also being mindful about how the Supreme Court’s decisions could affect the future of the nation.

“Even today, both sides feel they have something to learn from him and that makes him both important and fascinating.”